Compose Multiplatform for Web: An Amazing Framework That Maybe You Shouldn't Use

- Introduction

- Who am I?

- The issues with C4W

- Fullscreen canvas

- SEO / Indexing

- Download size

- Shared UI is overrated

- JavaScript Ecosystem

- Browser developer tools

- Initial render time

- Browser-managed features

- Accessibility

- International languages

- Conclusion

- C4W vs Compose HTML

- Sharing business logic

- Final thoughts

Introduction

The pitch for Compose Multiplatform for Web is attractive: write your code once, including UI, and share your application across multiple platforms, targeting Android, iOS, desktop, and, yes, even web.

We abbreviate "Compose Multiplatform for Web" as "C4W" for the rest of the article.

If you are an Android developer, you might think: "Wait, I can take my existing codebase and/or years of Jetpack Compose experience and have a working website with hardly any extra effort?? Sign me up please!"

If you run a startup, you might think: "I can hire just one programmer to build my mobile apps and website, pocketing the savings?? Sign me up please!"

In contrast, Compose HTML, an older, one-off Compose implementation that outputs an HTML DOM instead of rendering instructions, requires a significantly different approach, asking its developers to learn a foreign API as well as HTML / CSS and the JavaScript standard library (but Kotlin-ified). Any UI code written for Compose HTML cannot be shared with other platforms.

Perhaps it is no surprise then that Compose HTML has since been relegated to a blink-and-you-miss-it library section at the bottom of the Compose Multiplatform README.

And yet...

I think that choosing C4W could be a significantly time-consuming mistake for many Kotlin web projects and that most developers should seriously consider using Compose HTML instead.

Who am I?

I'm the author of Kobweb, a framework that layers opinionated decisions on top of Compose HTML to make it more enjoyable to work with and easier to get a site up and running quickly. (You can read more about it here.)

I have been working on Kobweb for three years at this point. So, I'm certainly biased, but I believe in the promise of Compose HTML. Otherwise, I would have abandoned this project long ago.

I have also paid attention to discussions that happened in the Kobweb community, as some users have tried out C4W and shared their experiences. They have helped shape the thoughts I will be sharing below.

The issues with C4W

Fullscreen canvas

When you create a C4W site, what you are fundamentally doing is creating a simple HTML page that hosts a single, fullscreen canvas element. You also download the script for the page itself as well as a rendering engine (Skia via Skiko) that allows C4W to draw to that canvas.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<script src="skiko.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<canvas id="ComposeTarget"></canvas>

<script src="site.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Canvases are backed by an image buffer, which can normally range from 8MB to 30MB depending on the user's window size. These buffers need to then be managed by the browsers, which have to make decisions on whether to keep them allocated or not when tabs are activated or deactivated. Buffers may need to be reallocated constantly when pages are resized as well.

When you right-click on a canvas, by default it presents options to the user as if they just right-clicked on an image. This means that users won't see the standard context menu full of browser options like "Open in new tab", "Copy link address", or "Inspect", unless properly intercepted and dutifully implemented by the framework.

Given that each browser has its own unique set of features and that some menu options may be provided by custom extensions, meeting the expectations of every user is an impossible task.

The fact that C4W relies on a canvas is also a root cause for many of the remaining issues we'll be discussing through the rest of this post.

SEO / Indexing

Perhaps the most important expectation that developers have when creating a website is that it will eventually be discoverable by search engines.

However, since C4W works by rendering into an opaque canvas, then any buttons, text, or other widgets that you create are not visible to search engines and cannot contribute to the page's indexing.

Once when I discussed this issue with someone from JetBrains, they mentioned plans to experiment with ways to address this, but it should be noted that Flutter (another framework which uses a fullscreen canvas approach) explicitly calls out that it is not SEO-friendly and is not trying to be.

If Google-backed Flutter never solved SEO, I am doubtful that JetBrains will be able to themselves.

Download size

A medium-size Compose HTML site compiles out to about 1MB, but this compresses well, generally resulting in a download size between 200-300K.

In contrast, when I checked a Flutter web app, it required a 2MB download for its rendering engine and an additional few hundred KB for the site itself.

A C4W app currently comes in at double that size, around 5MB. It is likely that the team will be able to shrink this size down in the future, but it is hard to imagine they will ever significantly improve past Flutter's current size, if they even manage to match it.

If you are paying for bandwidth or targeting users with poor internet, you should be aware that C4W likely has a floor that will always be 10-20x larger than Compose HTML.

Shared UI is overrated

I've heard promises sung about shared UIs my entire career, going all the way back to Java's 1995 "Write Once, Run Anywhere" slogan.

However, in reality, each target platform usually eventually demands its own custom UI codebase.

It is possible for early-stage products that a shared UI framework can help a small team reach a large number of users very quickly.

However, in general, as a product matures, its company will hire multiple teams to handle separate platforms. Each team can move a lot faster if they are allowed to progress independently, including making their own UI decisions.

While I worked at YouTube, a central team had spun up in order to serve all internal products UI layouts that they were supposed to follow. One goal of this approach was to ensure consistency across all platforms. However, in practice, various teams had unique hardware constraints or vastly differing user expectations, so those teams ended up telling the central team exactly what UIs they needed, and then they had to wait for the team to publish those layouts.

In other words, iterating required coordinating with one team busy servicing many other teams.

In retrospect, it would probably have been far less friction to let each team build their own UIs which then got reviewed by a central committee whose job was to verify shared UI guidelines.

Let's be honest: most programmers don't like writing UIs! It is slow, delicate work that is hard to test. To them, the promise of a shared UI framework is music to their ears.

That said, this is often a solution to the developer's problem, but users don't care about how stuff is built. They just want a product that works well and feels good on their preferred device. In many cases, shared UI codebases get the axe once user feedback across different platforms starts to stream in.

JavaScript Ecosystem

The JavaScript ecosystem is vast. Having access to it is a huge and underappreciated advantage for Kotlin/JS.

For example, I gave a talk about Kobweb at Droidcon SF '24, and I was confident before I even started working on it that I would be able to find a JavaScript library that would let me create slides.

Sure enough, I found Reveal.js and was able to integrate it quickly, building an initial proof of concept within a few hours.

I also use Highlight.js for syntax highlighting in this blog. Prism.js is another popular library in this space. Both are battle tested across a large number websites.

There are also many JavaScript graphics libraries out there that you can use to create stunning visual effects, charts, and images. In fact, Kobweb provides an OpenGL demo (run kobweb create examples/opengl to check it out) that uses WebGL to render a rotating cube.

All of these examples just scratch the surface and barely hint at all the possibilities of powerful JS libraries out there that you can use for free in your own site.

Perhaps over time, the number of Compose Multiplatform libraries with web support will grow, but even then, the JavaScript ecosystem has an absolutely massive head start, and it will only continue to grow at the same time.

Browser developer tools

Chrome and Firefox both come with a suite of excellent developer tools, letting you inspect your site's performance, layout and styles, memory usage, and network requests.

Among these, the Elements panel in Chrome and the Inspector panel in Firefox show you the DOM element tree of your site, letting you both understand how every element is styled as well as experiment with changing elements around quickly by tweaking the styles and seeing the effects in real time. These tools are rendered useless in C4W sites, since all styling happens inside the canvas.

Chrome also provides the comprehensive Lighthouse quality auditing tool, which gives you a score for how well your site is performing, how accessible it is, and how well it is optimized for search engines. This tool is a powerful way to quantify the health of your site, but it partially gives up when working with C4W sites as it can't draw much useful information about your actual content as it lives inside the opaque canvas.

Initial render time

A page's initial render happens when the browser finishes downloading your site. If any script tag is present, it will additionally be downloaded and run, often further modifying the page content.

With C4W and Compose HTML, the initial download will just result in a blank screen, since both approaches require executing code to populate the page. The page's script (and, in C4W's case, the rendering engine as well) need to be downloaded and run before anything will be displayed to the user.

Because the download size of C4W is so much larger than Compose HTML, this means that users will see a blank page for longer when they visit your site.

If you are using Kobweb on top of Compose HTML, it adds a step that exports your pages, taking a snapshot of each one and baking it into an HTML file. What this means is when you visit a Kobweb site, it will do an initial render as soon as the HTML itself finishes downloading, which will occur almost instantly. After that point, the page script will finish downloading and run, although this is generally invisible to the user since in most cases the script will simply recompute what is already being shown.

Kobweb's export process is only possible thanks to Compose HTML, since it works with the DOM. With C4W, users will simply have to wait for everything to finish downloading and the JavaScript to run before the page is populated.

Browser-managed features

Visited hyperlinks

The web is built on hyperlinks, which are a fundamental part of the experience. When a user sees a link, they expect it to show a color that indicates if they've visited before.

It turns out that, for security purposes, information about what links a user has visited is only known to the browser itself and not accessible to the developer. This is smart, as otherwise a malicious site could query a user's browsing history.

Therefore, in order to style unvisited and visited links differently, you must use CSS to style them. This lets you specify visited and unvisited colors, at which point the browser will apply them appropriately without needing to involve the developer.

Maybe this isn't a big deal in your site -- some sites intentionally disable visited link colors, for artistic purposes. If so, that's fine! But if this feature is important to you, then you should know that C4W is a non-starter.

Password autofill

When a user visits a site that has a password field, the browser can offer to autofill the password for the user.

With Compose HTML, you simply create two text inputs with their autocomplete parameters set (one to username and another to currentPassword) and they will automatically be integrated with the browser and populated with expected values.

As C4W uses its own custom password text field concepts, the browser won't be able to hook them up.

Accessibility

The web is built on the idea that everyone should be able to use it. As a result, it has multiple decades of accessibility design built into all browsers and many of the HTML elements that you use.

For example, if you use a <button> element, it will automatically be focusable and clickable by the keyboard. If you use an <input> element, it will automatically be focusable and allow the user to type into it.

Screen readers are also an important part of the web, allowing users with visual impairments to navigate and understand the content of your site.

When you run Lighthouse (see browser devtools▲), it will give you a score for how accessible your site is, helping you identify areas where you can improve or allowing you to feel confident that you are doing well.

Jetpack Compose, and C4W by extension, does support accessibility concepts, but users who depend strongly on accessibility tools may be surprised to find things working differently or not at all on a C4W site compared to most other sites.

International languages

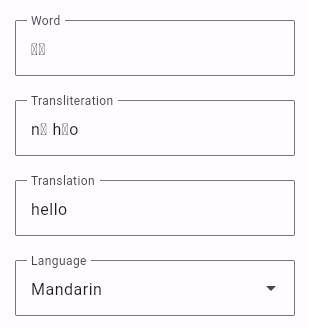

If you try to display, say, Chinese in C4W by default, you will see missing characters:

The above C4W example is failing to show "你好" and "nǐ hǎo" here.

To fix this, you'll need to load a font file that supports the characters you want to display and explicitly instantiate a Font value that uses it.

The default C4W font is presumably minimal to avoid adding to the site's download size significantly. Fonts that support Chinese characters easily clock in at least 10MB, which would be a huge waste for many users.

You might think, "OK, international fonts can be expensive to download, but if the application needs it, the programmer should just bite the bullet and include them, right?"

But what about cases where a user just wants to use your app, say for example a note-taking app, and they want to type some text in their own language? Or maybe you end up displaying some external content, like a news article or user comment, that happens to use international characters? Users will see ugly squares.

Simply put, your C4W site may unintentionally exclude users who expect international language support, and you might never know it unless a user happens to report it.

In contrast, Compose HTML (well, the web, really) defaults to using system fonts provided by the OS. Without any extra downloads or special work on your end, international text tends to just work out of the box.

Conclusion

For the reasons outlined above -- particularly SEO / indexing, download size, and access to the wider JS ecosystem -- I would argue that a majority of Kotlin web developers would be better served by using Compose HTML instead of Compose Multiplatform for Web.

Note that I've also heard developers mentioning that they encountered major issues when trying out C4W, as it is a framework that is still in an alpha state. Additionally, Wasm with Garbage Collection is currently in its infancy and, even at the time of writing this article, is not supported by Safari, which alone has been a deal-breaker for some.

However, I did not mention these issues because it feels like time will solve such problems.

In contrast, all issues I listed earlier will still be relevant even when C4W is stable and mature.

C4W vs Compose HTML

Now, if you ask me which API I think is better -- Jetpack Compose or Compose HTML -- I strongly prefer Jetpack Compose.

Jetpack Compose offers a more modern way to build UIs, benefiting from lessons learned by prior frameworks and providing very succinct and expressive layout primitives. Once you get your head around the basics, it is very intuitive to use and includes some incredible animation APIs.

In contrast, HTML/CSS carries a huge amount of legacy baggage. Sometimes you can feel trapped by decisions made decades ago, wading through features that span multiple eras and which occasionally provide a different experience depending on what browser you are using.

That said, Compose HTML treats the web as its own native platform, and, quite frankly, the web is a platform with significant strengths. Developers can benefit a lot from embracing it and can lose a lot by turning their back on it.

Of course, there are use-cases where C4W is definitely the right tool for the job!

As mentioned earlier, if you are an early stage startup, and you want to reach as many users as possible to demonstrate your application idea, Compose Multiplatform is a great solution.

Or maybe you are creating internal tools at your company. Writing a web app instead of a desktop application helps you ensure that everyone will always be up to date with latest. And with internal teams, you can require everyone use the latest Chrome or Firefox version without worrying about lost users.

Websites rendered in a canvas are a large niche currently well-served by Flutter, showing that it definitely has some demand. I would love to see C4W take on Flutter and win, since I think Kotlin is a more expressive and widely applicable language than Dart.

However, if you are building a website and not a generic application that just happens to be running on a web browser, Compose HTML is almost certainly the better choice.

Sharing business logic

Although choosing Compose HTML does require maintaining a separate UI codebase for your website, this does not mean that I am rejecting the idea of sharing code entirely.

In fact, Kotlin Multiplatform is a powerful way to share business logic across all platforms, and it is very applicable even with the web target.

For example, it could be a perfectly reasonable decision to use Compose Multiplatform for Android and iOS and then use Compose HTML for your website, at which point you could share a ton of common utility code between them.

In fact, Kobweb leans into Kotlin Multiplatform for fullstack websites, recommending users create serializable data classes in common code that can then be shared between the server (JVM) and client (Kotlin/JS) codebases. You could even use those data classes in your mobile apps which could then talk to a Kobweb backend web server!

Although sharing UI code may be overrated, sharing business logic is very effective and highly encouraged.

Final thoughts

Ultimately, I think both Compose HTML and C4W should exist. The technologies complement each other, and between the both of them, they empower any Kotlin web developer to accomplish whatever goal they might have!

I believe JetBrains should be more transparent about the tradeoffs and limitations of each approach, rather than only promoting C4W as a one-size-fits-all solution.

Until that happens, hopefully this article will help users make a more informed decision when starting their own Kotlin web projects.